Kevin Yusif Peña Aceves thought he belonged in his hometown of Albany, Ore. Growing up, he enjoyed life as an American, playing high school sports, teasing his three younger brothers, and hanging out with his friends. He expected to earn a driver’s license, find a job, graduate high school and head to college with the rest of his classmates.

But when Peña turned 16, his once-planned future dissolved.

Peña discovered he’d been living in the United States as an undocumented immigrant. Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, he’d flown to the United States with his parents when he was just 4 years old. His three younger brothers had been born on U.S. soil, but he’d grown up sheltered from his own status.

Peña couldn’t participate in any of the teenage milestones his friends were about to reach. Dreams of college turned to an uncertain past, hope diminishing into the fog of a murky future.

“For me it was like the biggest blow to know that even though I look like I’m from here and even though I feel like I’m from here and all my friends are from here, I’m not from here,” said Peña. “The country that I thought I belonged to or that I grew up in, all of a sudden I find out that laws are saying I shouldn’t be here and I can’t do what everyone around me is doing. My friends are going to college and I don’t even have the option to go to college or to get a job.”

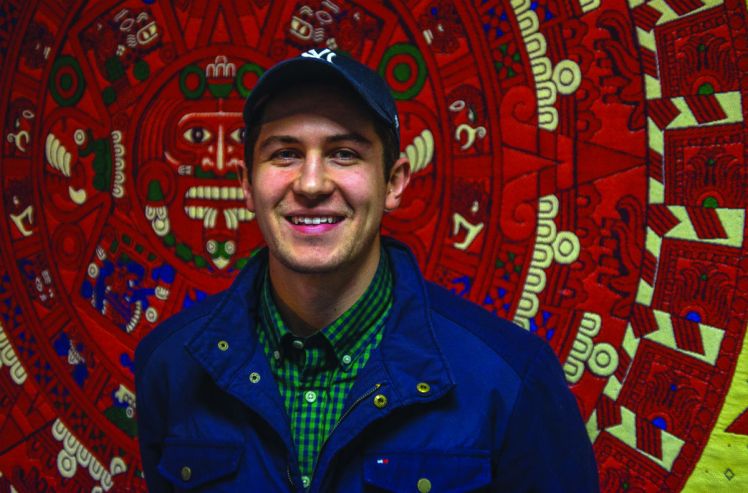

In present day, Peña, 26 years old, is LBCC’s student vice president, an integral part of the Student Leadership Council and an international student ambassador studying computer science and business. His six-year journey from undocumented high school student to documented international college student illustrates an underrepresented narrative in illegal immigration.

What if it was never a choice?

From Albany. Ore., to Denmark, Europe

With Mexican parents in an all-American hometown, Peña straddled two cultures, struggling with some of his parents’ perspectives as a teenager.

“I was very, very sheltered and so I think I started to rebel a little bit and go out and hang out with friends, even if my parents were telling me not to. They were probably just trying to keep me safe; it’s their culture to do so,” said Peña.

Distraught after the revelation of his documentation status, he left home to live with a friend, attending high school in Scio, Ore.

“At that moment, [because] I think I blamed my parents for it and I blamed my family for it, because it wasn’t a choice I made, and I didn’t see exactly what they were trying to accomplish,” said Peña. “Maybe you see it and you hear it; like you know they want a better life for you, but when you hear these things and then you see the reality of it, it’s like, man, how is this better than what I could have had in Mexico?”

Peña dedicated himself to school with newfound motivation.

“I think from day one I thought that [education] was the path to being able to overcome all of these things, gather knowledge and understand why these things were happening and be able to look for an option out,” he said.

Though he sought help from trusted faculty at his new high school, little came of it.

“I didn’t know what to expect — what reactions to expect — and every time I told the teacher, every time I told somebody I felt like I could confide in, I would get the same response, which is ‘I’m so sorry, I wish I could do something,’” said Peña.

He took matters into his own hands, with two options available: return to Mexico, or head to Denmark to stay with his aunt and uncle and seek an education there.

“I didn’t want to stay here in the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant and I didn’t want to experience having to be limited or having to always be running from the law or government and finding out a way to be sneaky… I felt like I had a lot more potential,” said Peña.

He flew to Denmark, his first travel experience outside the United States. After spending three months living with relatives he applied to the Copenhagen Business School and was accepted.

“Europe is beautiful and amazing and everyone wants to go there… I loved it and my aunt and uncle live super well,” said Peña.

The school required a student visa, and in the visa interview he was asked for proof of ability to support himself, needing $25,000 to obtain the visa. It wasn’t an option. Peña had one choice left: Return to Mexico.

Changes At Home

Meanwhile, Peña’s younger siblings struggled at home during his six-year absence.

Samy Cardenas Peña, the second-eldest of the four brothers, lost his role model and life-guide when his brother left. As a first generation child, the only person in Cardenas Peña’s family who could navigate the American school system had vanished. His father soon left too, leaving Cardenas Peña as the eldest.

He began caring for his two younger brothers in the ways Peña had helped him.

“I had to basically be a dad at like 13 years old or 14 years old,” said Cardenas Peña. “I focused on their sports, tried to make them smart, encouraged them to read… What I didn’t have growing up was someone who went through the school system, and that’s what I try to do for my brothers.”

Though Cardenas Peña missed his brother, the six-year absence forced him to mature.

“I think a lot of the pain that came was knowing that my mom couldn’t see him. I think that hurt me more than me not seeing him,” said Cardenas Peña, who is also currently a student at LBCC.

Culture Crash: Mexico

Peña landed in Mexico, crashing into a vivid culture shock.

“I was scared and I had a really bad perspective of what Mexico was going to bring,” said Peña.

He saw little reason to return to a place from which his mother had fled. Staying with his maternal grandparents, Peña began to understand a fuller scope of his heritage.

“It’s very, very humble. I was sharing a room with another family member,” said Peña.

The neighborhood was poor, and the home was infested with cockroaches. Via social media he watched his friends living out his dreams of the college experience back home, thinking, “Why don’t I get to have that? Why is it that my life has to be this way?”

Now, on the other side of the culture shock, Peña rejects this self-victimization.

“I value a lot of what I went through. Every single thing that I went through I can look back honestly and say you know, I won’t make that same mistake again,” said Peña. “I catch myself now whenever I’m feeling in this victim mindset; I hate it and it happens because I think it’s human to kind of just put yourself there. It’s almost like an easy route.”

But Peña was young, and struggling with confidence.

“For me at the time it was a drastic change and like nothing I had ever experienced. It was really, really like the bottom; I hit bottom and it was hard and it was depressing,” said Peña.

He had no idea what to do next.

“I already had my mindset that everything was going to be a closed door again, another thing that just was going to go wrong at this point, and that’s when I got super lucky.”

Gambling for a Future: A Lucky Stint

Peña landed a job with a developing casino company, Grupo Win.

It was 2011 and the Mexican federal government just opened permits and licensing for casino table games.

“I got in at the very beginning. We built this huge team, and I started as a casino dealer,” said Peña.

The business moved fast, and Peña traveled Mexico with Las Vegas-based owner Patrick Differ training teams and opening tables at casinos. Peña’s perfect English gave him an edge with the boss.

“It was from ground zero. I took advantage of that and I really, really tried my hardest. I was training and I’d go home and practice everything and I’d come back and I was above and beyond what every other one of the dealers was doing,” said Peña.

He stayed after 12-hour shifts, learning cold-counting and administrative work as he shadowed his boss, taking notes, eventually opening a casino on his own while his boss was away, opening a larger casino.

At 20 years old he was making good money and promoted to rotating pit boss, a type of casino manager. He’d found a return of hope and confidence.

Just before a federal shutdown of casinos took place after exposed government corruption, Peña met a congressman at his blackjack table, Daniel Ochoa Casillas. After several conversations, Casillas invited Peña to meet political candidate Aristoteles Sandoval Diaz, a candidate for governor in the state of Jalisco.

From Dealer to Dreamer: A Political Process

Casinos shut down and out of work, Peña decided to take a chance on Casillas’ offer. He had little to lose on a meeting.

“I’d never worked in politics; I’d never even really had an interest in politics before this. The only thing I remembered [was that] in Scio I’d taken a couple photography classes,” said Peña.

The classes were his golden ticket; Diaz hired Peña as a campaign photographer. Yet this was another gamble for Peña; campaign workers weren’t paid, just given food and phone cards on the trail. The payoff only happens with a campaign win.

“I ended up spending all of my savings because it was almost three or four months of campaigning without any income,” said Peña. “I was just hoping that I’d get an opportunity to work and land a job in government.”

Peña’s gamble did pay off. On March 1, 2012, Diaz was inaugurated as governor of Jalisco, and he’d hired Peña to continue as a photographer and social media consultant.

“That [inauguration] was the first day I got to be at the state government palace. I was suited up, red tie, white shirt, black suit, and this is not very common for me, but I felt just like ‘How the hell did I get here? How did I do this?’” said Peña.

He continued working for Diaz for four years, from 2012 to February 2016, promoted to second assistant after two years.

Despite career success, Peña still dreamed of college and a reunion with family. His two previous tourist visa applications were denied, so he built up the courage to ask the governor to send a letter of recommendation to the U.S. Consulate in Guadalajara.

A Rosy Reunion

“Honestly, that room [U.S. Consulate] is the worst room to ever sit in. It’s just this open space and it has just chairs, lines of chairs,” said Peña.

After two previous visa denials, Peña sat in the room, anxiety festering. He watched families ahead being questioned, some turning away with tears in their eyes, some smiling.

“What you hear is that they can detect everything, they can smell fear from like a mile away, these immigration officials. So you go up there and you try to act like, you know, I don’t even want to go to your country. That’s the way you have to act, so it’s kind of scary,” said Peña.

But with the recommendation, the process was smooth, and the immigration official led him through the questioning, telling Peña how to respond so they could accept his visa.

Visa approved, he called his younger brother and planned a surprise visit to Albany to see his mother.

In August 2016, Peña walked into his mother’s workplace with six dozen roses filling his arms, a dozen for each year he’d been absent.

“My mom sees me and I’m standing there with six dozen roses, expecting her to grab the roses, but instead of grabbing the roses — she didn’t even look at them — she just grabs me and starts crying,” said Peña. “It was one of the most amazing moments I think I’ve ever had, connecting with my mom again.”

“My mom sees me and I’m standing there with six dozen roses, expecting her to grab the roses, but instead of grabbing the roses — she didn’t even look at them — she just grabs me and starts crying,” said Peña. “It was one of the most amazing moments I think I’ve ever had, connecting with my mom again.”

Eyes on the Horizon: What’s in Store?

Peña returned to Mexico, but with another recommendation from Diaz, and a bank account with $23,000 saved, he acquired a student visa. Applying to LBCC, he connected with Sharece Bunn, international student coordinator, and began his career as a Linn-Benton student in the spring of 2016.

“I think by getting involved in the social issues of our time and sharing his story, Kevin is challenging the dominant paradigms that continue to perpetuate the injustices our immigration system and borders provide for folks around the globe,” said Bunn.

While Peña’s exact future is still unclear, he intends to pursue college in the United States at a four-year institution.

With Trump-era immigration policies now at play, he may face future adversity. But for now, his hard-won student visa grants him the right to pursue his education in the United States.

“Everyone around us is just kind of scared. Even if they are here legally, they know someone who’s here illegally,” said Cardenas Peña. “Everyone knows someone who’s illegal, even if they know they’re illegal or not. Sometimes you’re not in charge of that, like my brother’s situation. He had no control. I think people need to understand that it’s more than just one scenario. It’s not black and white. There are so many in-betweens. Some people can’t get their citizenship. It not only takes connections, it takes money, and some people just don’t have that.”

After such a long journey home, Peña remains undaunted.

“When something seems unachievable, you can either decide it’s because of what my life situation is, or, regardless of my life situation, I’m going to do it. I’m going to prove everyone wrong,” said Peña. “I think along the way what I’ve learned is that you always have a choice… one might be a lot harder and take a lot longer, but you always have a choice.”

Story by Emily Goodykoontz

Reblogged this on My Heart of Mexico and commented:

As untold numbers of Dreamers face uncertainty in the USA, this story should inspire them to have hope and never give up!

LikeLike